- Home

- Jerry Bledsoe

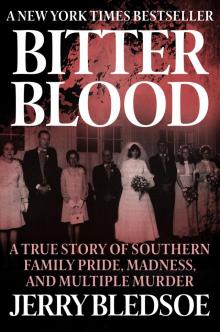

Bitter Blood

Bitter Blood Read online

Bitter Blood

A True Story of Southern Family Pride, Madness, and Multiple Murder

Jerry Bledsoe

Copyright

Diversion Books

A Division of Diversion Publishing Corp.

443 Park Avenue South, Suite 1008

New York, NY 10016

www.DiversionBooks.com

Copyright © 1988 by Jerry Bledsoe

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

For more information, email [email protected]

First Diversion Books edition May 2014

ISBN: 978-1-62681-286-4

More from Jerry Bledsoe

Before He Wakes

Blood Games

Death Sentence

for Linda, who loved me and endured,

and for Erik, who kept the computer functioning

“And I stood upon the sand of the sea, and saw a beast rise up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns and upon his horns ten crowns, and upon his heads the name of blasphemy.”

—REVELATION 13:1

Part One

The House on Covered Bridge Road

1

Delores was late. That was unlike her, and Marjorie Chinnock was concerned.

Marjorie and Delores Lynch met every Sunday morning in the parking lot of Grace Episcopal, a small granite church in south Louisville. Usually, Marjorie arrived first and waited for Delores’s car to come down the long drive to the back of the church. Delores would park beside her and they would go inside, where Delores always went to the rest room before they entered the sanctuary. After the thirty-minute service, they would join other church members in the parish hall for coffee, a time Delores particularly enjoyed. Unlike Marjorie, Delores was gregarious and often made herself the center of attention at these gatherings. Afterward, she and Marjorie would walk to their cars and chat until Delores said, “Well, I must go. Janie will have our doughnuts.”

Delores lived in a country house seventeen miles from the church, and during the three years she and Marjorie had been attending church together, her daughter, Janie, had been a student at the University of Louisville’s School of Dentistry, training for her third career. Janie had a student apartment at the downtown campus, but she often spent weekends at home. On those days, while her mother was at church, she would drive to Ehrler’s Dairy Store in Prospect and buy yeast doughnuts, only two, and have them ready with coffee when her mother got home. When Janie wasn’t home weekends, she often drove out to spend Sunday mornings with her mother, stopping for the doughnuts on the way. Later, Delores and Janie would drive back to Louisville to the House of Hunan for the Sunday lunch special.

For Delores, the day provided a satisfying weekly ritual.

She craved ritual. Indeed, it was the reason she belonged to Grace Episcopal. When the Episcopal church adopted a new prayer book, Grace defied the diocese and refused to accept it, clinging to the more ritualistic liturgy of the 1928 prayer book, a defiance that eventually would cause Grace Episcopal to disaffiliate itself from the diocese. Grace was the first church Delores attended regularly after moving to Louisville in 1967, but she left it in 1969 because she didn’t like the priest. He looked “greasy,” she complained, and she felt dirty after shaking his hand. That was something that Delores, with her obsession for cleanliness, couldn’t abide.

She attended several churches before settling at St. James Episcopal in Pewee Valley, a tiny town northeast of Louisville, much closer to her home. But eventually she would leave that church also—in bitterness. Made a rebel by her conservatism, she had returned to Grace five years earlier, in 1979, because of the maverick stand the church took on the prayer book issue. The “greasy” priest had departed, and she now felt comfortable at Grace.

Marjorie Chinnock met Delores in 1967, when she originally came to Grace. At first, Marjorie didn’t understand why Delores sought her friendship. Marjorie was reserved, almost withdrawn. And she was far from being on the same financial footing as Delores, the wife of a top General Electric executive. Delores lived then on stock dividends and a monthly allowance from her husband in an expensive home on the grounds of a prestigious country club. Marjorie, a divorced mother of grown children, lived in a modest apartment in an older section of Louisville and worked at a Kroger supermarket.

This is strange, Marjorie told herself at the beginning of the relationship. Why does she seek me out? I’m a working person. She belongs in a high echelon. Doesn’t she know who she is?

But after careful consideration, she began to think: Maybe I’m the snob, and accepted Delores’s friendship without question. After Delores left Grace Episcopal, the two friends gradually drifted apart, and Marjorie had been surprised three years earlier to get a call from Delores. Disenchanted, Marjorie had left the church altogether in 1970, and Delores had never questioned why until she called that Sunday afternoon.

“You were always such a devout Episcopalian,” Delores said. “Why don’t you come back? Meet me in the parking lot next Sunday.”

Marjorie did, and their Sunday mornings became ritual.

But on this morning, the fourth Sunday of July 1984, Delores was late. Marjorie kept looking impatiently at her watch as time for the 8 A.M service neared. Finally, she decided she could wait no longer. She would not be late. She went inside, and just as the service was about to begin, Delores slid into the pew beside her, smiling apologies.

After the service, conducted by a visiting priest from Cincinnati because the regular priest was on vacation, Delores explained that she just had been running behind. She was her usual self at coffee, flitting about, joking and laughing and talking loudly—the usual Sunday morning chitchat that nobody would recall later. Marjorie noticed that Delores’s two-piece dress, a wispy thin print of tiny blue and red flowers, didn’t match. The top was faded, as if it had been washed more than the bottom. That was nothing unusual, Marjorie knew, for despite her obvious wealth Delores bought all of her clothes at discount houses and bargain shops and wore them long past their fashionable usefulness.

As always, Delores and Marjorie walked to their cars together and stood between them to chat. Delores was excited about the impending visit of her son, Tom—TJ, she called him—of whom she frequently boasted. He was due to arrive Friday from Albuquerque with his new wife, Kathy, and two sons from a previous marriage, grandchildren Delores rarely got to see. Three days earlier, Janie, fresh from taking her final tests to practice dentistry in Kentucky, had moved her belongings from her university apartment back into the house. The house was a mess, Delores said, and there was much to be done before Tom arrived.

Delores complained constantly about the demands her house made on her—especially since she’d given up her once-a-week maid—but until recently Marjorie had had no idea of the scope of those demands because she’d never been to the house. But two weeks earlier, as she and Delores were leaving church, Delores had said, “Why don’t you come and have breakfast with me at the house?”

Marjorie was delighted to accept, and Delores went back into the church to call Janie and tell her to forget the doughnuts. They rode in the seven-year-old gray Volkswagen Dasher that had belonged to Delores’s husband. As they pulled into the long driveway to the house, Marjorie took one look and said, “Delores, what’s the name of this hotel?”

The house did bear some resemblance to a Ramada Inn. Set on four and a half acres of wooded hillside, it was a sprawling ranch house of pink brick with white shutters and wrought iron grillwork, two stories, fourteen rooms, four and a half baths—and Delores had been its sole occupant since the death of her husband, Chuck, eight months earlier.

Delores laughed. “I ride the m

ower four days a week,” she said.

Two Sunday mornings later, as Delores stood complaining about the size of the house and her fear of being in it alone, Marjorie said, “Delores, why don’t you just get rid of it? You’re a prisoner of that house.” She knew that Delores had wired her home with elaborate alarms, had outfitted it with strong locks, and was scared to the point of paranoia about somebody breaking in on her.

“No, it’s not that house that makes me a prisoner,” Delores said. “It’s criminals that make me a prisoner.”

Later, Marjorie recalled that it must have been about 10 A.M. when Delores uttered her routine line about Janie and the doughnuts and departed with a wave. The next time Marjorie saw her friend, Delores would be on the TV news and Marjorie would recognize her only by the mismatched dress she had worn to church that Sunday.

About 10:30 that morning, Delores pulled up to the gas pumps at the Prospect Chevron station on U.S. 42, only a few miles from her house. She stopped regularly at the station, had minor work done on her cars there, and the station’s young employees all knew and liked her. Delores was sixty-eight, but she acted much younger than her years. A tiny, trim woman whose short hair still showed as much brown as gray, she was lively and entertaining, always talking and joking with the young men at the station, even occasionally offering advice about personal problems. Butch Rice, the station’s twenty-two-year-old assistant manager, a thin man with a mustache, always looked forward to Delores’s visits—“She was like a mother to me,” he said—and he hurried out to wait on her.

Delores got out of the car as usual and commented about what a pleasant day it was now that clouds had moved in and the scorching heat of previous days had dissipated. The weatherman had said the temperature would climb only to 80 this day, and with little sun it would be a good day for working outside. Delores wanted Butch to put some gas for her riding mower into a red can in the back of the car. She gave him the keys and went inside to say hello to the other guys working that morning. She paid with her Chevron credit card, and as she started to pull away, Butch leaned down and said, “Have a nice day, Mrs. Lynch.”

She smiled. “You too.”

Delores drove south from the station to the intersection of State Road 329, known locally as Covered Bridge Road but not marked so by signs. It is a picturesque country lane: narrow, curvy, hilly, with no shoulders. From its first mile at U.S. 42, trees, many of them huge sycamores, grow fast by the pavement, their branches overhanging the road from both sides, giving it a tunnel effect, cool and soothing on a hot summer day. Soon after the road passes out of Jefferson County with its urban sprawl into rustic Oldham County, it opens onto big horse and cattle farms, the rolling green hills patterned by dark wooden fences. It passes an expensive new subdivision before dipping around a sharp curve and crossing Harrod’s Creek, where once stood the covered bridge that gave the road its name. The bridge was replaced long ago by a dangerous, one-lane bridge with an overhead framework. (Called the Old Iron Bridge, it, too, was about to be relieved by a wide, modern concrete bridge then under construction.)

Just beyond the bridge is the entrance to the Boy Scout camp where a week earlier Delores’s 1977 Oldsmobile had broken down, leading to an angry dispute with the camp’s caretaker that had left her ranting and threatening to call the police and sue for damages (The caretaker had used a tractor to push the abandoned car a few feet to keep it from blocking the camp entrance.)

From the creek, the road continues alongside a small, lazy stream that meanders to the creek, passing over several miniature waterfalls as it goes. The creek winds through Delores’s front yard, and she followed it the last mile home, stopping at the top of the driveway to fetch the fat Sunday edition of the Courier-Journal from her roadside box.

The asphalt driveway went downhill, across the small stream over a wooden bridge, then uphill to the house, where it formed a loop at the front entrance with its iron-barred double doors. A branch of the drive continued up the hill to a wide parking area adjoining the house. The first level of the house on that end was a two-car garage, which never housed cars. Delores kept its concrete floor waxed and used it only for storage—everything neatly boxed, labeled, and stacked, although it was in some disorder then from Janie’s belongings, which the movers had deposited there three days earlier. Between the double, roll-up garage doors was a white wooden door that Delores and family members used as the main entrance to the house. Anybody inserting a key into that door had twenty seconds to walk across the garage and flick a switch to keep the alarm from sounding.

Delores pulled the Volkswagen between her recently repaired green Oldsmobile Cutlass and Janie’s 1970 gold Chevrolet Nova. She got out carrying her beige purse, a yellow-bound Bible, the Sunday paper, the gas receipt, the white sweater she’d carried against the morning coolness, and her keys on two rings held together by a safety pin. She was about to insert one of those keys into the center garage door when a shot rang out, splattering the door with her blood. The shot was followed quickly by another, and a few seconds later by a third.

2

When Delores Lynch moved into the big house on Covered Bridge Road late in 1970, she vowed that this was the last move she would make. She was fifty-four, her children were grown, and every time she had begun to establish roots, she had been yanked up and moved. She resented it. Needing order and stability, she felt haunted by change.

Not since her early childhood in Pittsburgh’s east end had she had security of place. Her father, John Rodgers, a machinist at Union Switch and Signal Company, had died in 1932 when Delores was fifteen, leaving his wife, Lilie, and two teenage children to fend for themselves in the depths of the Depression. Delores’s brother, Elmer, three years older, took upon himself the responsibility of seeing that the family had a roof over their heads and food on the table—and that his younger sister would be able to stay in Westinghouse High School and eventually achieve her dream of becoming a nurse. But work was scarce, pay short, and as the family’s situation steadily deteriorated, they were forced to move several times. The hardships of those years would have a lifelong effect on Delores, who decades later still proclaimed that nobody ever lived poorer than she. “I know the value of a dollar,” she enjoyed telling people. “I lived through the Depression.”

Delores didn’t get along with her mother and seldom talked about her childhood in later years. If anybody asked about it, even her children, she changed the subject. When her mother died in 1974, she mentioned it to none of her friends.

Near the Depression’s end, Delores’s brother became a Sealtest milk routeman, a job he would keep until his retirement, and he was able to help his sister complete her nursing training at Pittsburgh’s Mercy Hospital. Soon after she started to work as a nurse at the hospital, a friend invited her on a blind date, and she met the man she would marry.

Charles R. Lynch, Jr., grew up in the steel mill town of Vandergrift, thirty miles northeast of Pittsburgh. His father was a chemist in the mill laboratory. The second of seven children, Chuck, as he was to be called throughout his life, grew up loving sports. Although he was a wiry five-foot-three, his pugnacious nature allowed him to claim a spot as a starting guard on the basketball team at Vandergrift High and to become a bantamweight Golden Gloves boxer. But it was in academics that he really excelled, and he was rewarded with a scholarship at the University of Pittsburgh, where he became a business major.

After his graduation, Chuck went to work as an accountant at the General Electric plant in Pittsburgh, but the coming of World War II prompted quick decisions. He enlisted in the navy and asked Delores to marry him. The wedding took place on January 11, 1942, at his family’s Evangelical and Reformed Church in Vandergrift. Chuck spent most of the next three years at sea guarding Atlantic convoys and rising to the rank of chief petty officer, while Delores lived near his home port in New Jersey, working as a nurse until the birth of her first child, Jane Alda, on October 28, 1944. At the war’s end, Chuck returned to his new fa

mily and his old job at GE.

Before his son, Thomas John, was born on August 16, 1947, Chuck was already a young man on the rise at GE. After taking the company’s business training course, he was assigned to GE’s staff of traveling auditors at the huge plant in Schenectady, New York, where Thomas Edison had started the company in 1886. This was a plum assignment for promising would-be executives, and Chuck was proud to get it. The traveling auditors were dispatched to GE plants all over the world and often were away from home for months at a time. Delores resented being left alone with two small children and grew bitter about it.

After three years as an auditor, Chuck got a quick succession of assignments in New York and New Jersey. He moved his family four times in three years, living for the longest stretch—two years—in Livingston, New Jersey, before he got his first management job at a GE distribution center in Washington D.C. The family settled in Springfield, Maryland, for the next three years. The constant moving didn’t bother Chuck. It was a price he expected to pay for his ambition. He was the quintessential company man, willing to give whatever the company asked. “He lived for GE,” a friend said of him after his death. “GE was his life.”

Chuck’s dedication paid off with a promotion and a transfer to Chicago, where he was to become distribution manager for GE’s Hotpoint appliance division. The family settled into a comfortable, two-story older house with a lawn and trees on Hoyne Drive in south Chicago, and Chuck, a golfer, joined the nearby prestigious Midlothian Country Club. Janie and Tom had attended private schools in Washington, and in Chicago both were enrolled at Morgan Park Academy, only a few blocks from their home. Here the family was to achieve its longest period of stability, nearly six years.

Bitter Blood

Bitter Blood